Inquiry

2011 The Global Nuclear Future

Inquiry 2010-11

The Global Nuclear Future

I have felt it myself, the glitter of nuclear weapons. It is irresistible if you come to them as a scientist. To feel it’s there in your hands, to release this energy that fuels the stars, to let it do your bidding. To perform these miracles, to lift a million tons of rock into the sky. It is something that gives people an illusion of illimitable power, and it is, in some ways, responsible for all our trouble--this, what you might call technical arrogance, that overcomes people when they see what they can do with their minds.

--Freeman Dyson

Against the backdrop of the nuclear arc of the history of the race for the atomic bomb and the secrecy and espionage of the Manhattan Project to President Obama’s 2010 Nuclear Security Summit and beyond, EPIIC will explore our global nuclear future.

Nine countries control 23,000 nuclear weapons. During the Cold War, world superpowers amassed nuclear arsenals containing the explosive power of one million Hiroshimas. Two decades after the end of the Cold War the U.S. and Russia still have a combined total of more than 20,000 nuclear weapons. The American Academy in Berlin recently asserted that a Hiroshima size weapon detonated from inside the back of a large van in London’s Trafalgar Square in the middle of a workday would cause an estimated 115,000 fatalities and another 149,000 injuries from a combination of blasts, fire, and radiation poisoning.

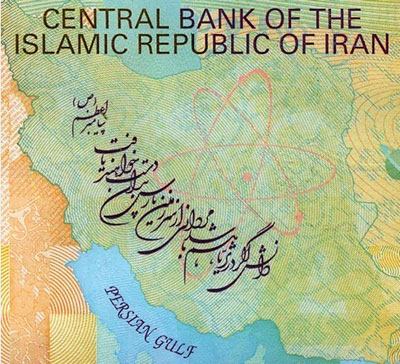

We will look at the history of failed and successful arms control regimes, the threat posed by both declining and rising nuclear states, how nuclear terror and catastrophe are rendered in popular culture, the dilemma of science in the service of military objectives, resource wars in Africa and elsewhere to control and exploit uranium, Israel’s Osirak raid and concerns over temptations of preemptive strikes and preventive war, the proclaimed “nuclear renaissance” and the building of new nuclear energy plants, the relevance and ethics of deterrence thinking, and the political, diplomatic, civil and military complexities of proliferation case studies, including Pakistan, South Africa, Libya, Iran, and North Korea.

Some of the questions we will explore include

-

Is nuclear terrorism the most pressing, dangerous and neglected feature of our world’s nuclear predicament?

-

Is there a future for the Non-Proliferation Treaty?

-

Why hasn’t the US ratified the 2005 Nuclear Terrorism convention that requires all states to criminalize unlawful use of, and possession of nuclear material, or damage to nuclear facilities?

-

Will the U.S./Russian START agreements diminish nuclear stockpiles?

-

Why have sanction regimes been so futile in preventing proliferation?

-

How can the massive and aging nuclear arsenal of the cold war be revamped to address the challenges posed by suicidal terrorists and unfriendly regimes seeking nuclear weapons?

-

Is a nuclear-free world actually attainable?

-

What are China’s and Japan’s reactions to the North Korean nuclear capacity?

-

What is the psychology of nuclear proliferation?

-

What are the concerns over China’s Taibai Mountain? Over Yucca Mountain in the US?

-

What do European countries think about the U.S. decision to abandon the European theater missile shield?

-

Are the experts and editors of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists justified in moving back the minute hand on the “Doomsday” clock?

-

How realistic is the threat of a terrorist suitcase bomb? How major a threat would be posed by an electromagnetic pulse attack?

-

What is the status and likely outcome of ongoing Iran nuclear negotiations?

-

How effective are citizen action movements such as the Nuclear Freeze Movement and the Global Zero initiative?

-

What are the realistic and unrealistic goals of President Obama’s four-year plan?

-

How vulnerable and how much of a threat are nuclear reactor laboratories, like the one at MIT?

-

How does Japan, Poland, or the Czech Republic feel about the efficacy, the necessity of the US or NATO nuclear shield?

-

What did the world learn from the search for weapons of mass destructions (WMDs) in Iraq?

2011 Inquiry Roles

|

MENTOR |

SCHOOL |

ROLE |

SCHOOL |

MENTOR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Kelly, Emily Roston |

Brookline |

United States |

Boston Latin HS |

Dan Rizzo |

|

Daniel Lakin |

Columbia Prep |

Russia |

Lawrence Central HS |

Peter Segall |

|

Nunu Luo |

Little Village |

China |

Pace |

Angelina Garneva |

|

Katie Tajer |

Jones |

UK |

|

|

|

|

|

France |

Medford HS |

Patrick Schmidt, Alexa Petersen |

|

Alyssa Wohlfahrt |

Dover Sherborn |

Pakistan |

Dover Sherborn |

Asad Badruddin |

|

Averi Becque |

O'Bryant |

India |

Stuyvesant |

Yamila Irizarry-Gerould |

|

Jon Garbose |

Pace |

Israel |

Packer Collegiate |

Avantha Arachchi |

|

Vijay Saraswat |

Windham HS |

North Korea |

Columbia Prep |

Seth Teleky |

|

Lindsay Semel |

Phillips Exeter |

Iran |

O'Bryant |

Logan Cotton |

|

Cullan Riley |

Broad Ripple HS |

Japan |

HSTAT |

Eve Lifson |

|

Joel Wasserman |

Dover Sherborn |

South Korea |

Dover Sherborn |

Chelsea Brown |

|

Ellie Caple |

El Puente Academy |

South Africa |

Banana Kelly |

Roy Loewenstein |

|

Mine Kansu |

Boston Latin HS |

IAEA |

Cristo Rey |

Will Shira |

|

Julia Bordin |

HSTAT |

Brazil |

Jones |

Jessie Wang |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COMMITTEES |

|

|

|

|

|

Disaster Response and Preparedness |

|

|

|

|

|

Black Market |

|

|

|

|

|

Economic Implications |

|

|

|

|

|

Reassessing Safeguards |

|

|

|

|

|

Military Response and Coordination/Threat Assessment |

|

|

|

|

|

Implications of Failed States |

|

|

|

|

To download the questions, scroll to the bottom of the page and click the download link

INQUIRY 2010-11

Conference on Nuclear Terrorism Preparedness and Response

April 7-9, 2011

A Nuclear Security Summit

the United Nations

Dear Delegates:

Unexpected situations and turmoil can arise at any time. Events such as today’s earthquake and tsunami in Japan and the ongoing tumult in the Middle East can shake the foundations of countries’ security and disrupt the global economy. Given these recent events, the United Nations has decided to build on US President Barack Obama’s efforts to address the nuclear issues of the day by continuing the Nuclear Security Summit. All of you have agreed to join us in discussing what may be the most urgent terrorist threat – that of a nuclear detonation. We thank you for your willingness to participate and your commitment to moving the dialogue forward. Below are the issues that will be addressed in each of the committees during the conference. We look forward to seeing you in April.

Sincerely,

Averi Beque

Jon Garbose

Daniel Lakin

Cullen Riley

Dan Rizzo

Patrick Schmidt

Lindsay Semel

• • •

Disaster Response and Preparedness Committee

Once a nuclear attack has happened it is important to begin search and rescue operations as quickly as possible. Many people will be in need of immediate medical attention, trapped in unstable buildings, or in some other not immediately accessible area. On the other hand, however, the blast area will still be very dangerous in the immediate aftermath of an attack. Buildings may continue to collapse, fires may spread, and many areas will still be dangerously radioactive. First responders may suffer in large numbers. How should the need to reach and help survivors as quickly as possible be balanced against caution in the immediate aftermath of a nuclear attack?

The delegates are asked to determine how countries and international bodies should respond in the immediate aftermath of an attack.

In the event of a terrorist nuclear attack or a nuclear accident, it will be important for all nations to help as effectively and forcefully as possible. For example today there are only 1,800 burn beds in the US today. What is the best way to coordinate the international community’s many resources into a coherent aid effort?

The delegates are asked to develop a global database of what countries can provide in response to a potential nuclear attack, from medical supplies to food reserves to evacuation vehicles and support.

After the Chernobyl explosion in April 1986, clouds of radiation drifted over Europe, affecting West Germany particularly strongly. Although West German disaster management efforts began almost immediately, there was a great deal of confusion and poor coordination between the various levels of government and between governments.

The delegates are asked to construct a communication network plan so that international efforts and information mesh, leading to the greatest number of lives being saved and the minimum amount of time being wasted.

In the aftermath of a nuclear terrorist attack, it is all too easy to imagine that more similar attacks might be on their way around the world. Many countries, particularly those that have been victims of terrorism before, will be rightly concerned for the safety of their cities and people.

The delegates are asked to determine what steps the international community can take to prepare for additional attacks, while still focusing on the attack that has already happene

Military Response and Coordination/Threat Assessment Committee

The number of terrorist attacks in recent years has increased. With the gravity and occurrence of terrorist attacks increasing and showing no signs of decline, a military response to each serious terrorist attack is going to be out of the question. What is the likelihood of another terrorist attack in the near future? Will it always be practical or feasible to respond militarily to every terrorist attack? Recent events have shown that traditional conventional warfare is not the most effective way to combat terrorism. In the event of a nuclear terrorist attack, it is very likely that there will be little or no evidence as to who was responsible for detonating a nuclear device, whether it is a state or non-state actor. Would nuclear retaliation be an appropriate response for any or every nuclear scenario? What would the successful detonation of a nuclear device mean for nuclear deterrence? What level of military response is acceptable or applicable to a terrorist detonation of a nuclear device or rogue state proliferation? The military will also have to prepare for the eventuality that any nuclear attack is not a singular attack and it could be part of a coordinated campaign or operation.

The delegates are asked to determine a protocol for an international response to a nuclear terrorist attack.

In many humanitarian disasters, the military has played a crucial role in recovery and reconstruction efforts, most recently in the 2010 Haiti Earthquake. In any major disaster, there is a chain of command established in order to keep the numerous government and military organizations on task and under control. Should there be an international military response team similar to international peacekeeping missions in the event of a nuclear attack? Should the military be given priority over local responders? Given the unique mobility and equipment available only to the military, should the military assist and/or lead recovery efforts or should a civilian organization?

The delegates are asked to determine the necessity of an international military response team focused solely on nuclear terrorism.

In many terrorist attacks, there has been advance intelligence that hints at the possibility of future attacks. While not all of these advance tips are credible and it would be impossible for any intelligence agency to thoroughly investigate, how can threats be better assessed in the future to prevent another nuclear catastrophe? How can intelligence agencies better prepare themselves to assess threats in a timelier manner to prevent future attacks? After 9/11, the main intelligence agencies in the United States underwent several changes in order to provide better information and improve their capabilities. After a terrorist nuclear attack, whether domestic or foreign, it will have profound changes on how intelligence agencies operate. Would intelligence sharing internationally be beneficial or harmful to any nation?

The delegates are asked to consider the feasibility and desirability of a new protocol for international intelligence sharing.

Reassessing Safeguards Committee

Since its founding in the late 1950’s, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has played a central role in ensuring the international peaceful use of nuclear power. Since the near universal acceptance of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, it has also been set with the task of verifying that non-nuclear weapons states uphold their obligation not to convert nuclear technology to weapons purposes. Today, its mission has been formalized into three pillars – Safety and Security, Science and Technology, and Safeguards and Verification. The IAEA’s ability to effectively uphold the last of these pillars – safeguards and verification – has often been the subject of scrutiny. Indeed, it has been shown in the past that non-nuclear weapons states that are signatories to the NPT can develop covert nuclear weapons programs without the knowledge of the IAEA. Though there have been some efforts to bolster the IAEA’s authority, such as the Additional Protocol, some still doubt its capacity to stop a determined state from developing nuclear weapons. In light of the potential flaws in this system, can the authority of the IAEA, or any international organization, be strengthened to the extent that peaceful use can be satisfactorily verified? Do existing norms within the IAEA framework suffice? Is there a limit to which states will agree to allow IAEA intrusion? Is there such a thing as verification that can satisfy all parties to the IAEA? What would effectiveness and equitability coexist within a strengthened safeguards system?

Delegates are asked to discuss the effectiveness and equitability of current IAEA safeguards, and possible modes of improving them. Additionally, delegates are asked to consider the meaning of the word “verification,” and whether peaceful-use can truly be verified within a certainty that allows member states doubtless

Today, the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty is nearly universally accepted by the world’s nations. Its mission has been categorized into three pillars – nonproliferation, disarmament, and the right to peacefully use of nuclear technology. Interestingly, verification measures, as mediated by the IAEA, only seek to ensure that non-nuclear weapons (NNWS) states do not convert nuclear technology to weapons purposes. Furthermore, those NNWS found to be in non-compliance of the NPT are referred to the UN Security Council for punishment. Yet, the only permanent members of the UN Security Council are the 5 NPT-recognized nuclear weapons states (also called the P5 – US, UK, Russia, France, and China), who themselves answer to no one if they do not undertake to disarm as agreed upon under the NPT. Thus, many see an inherent inequality within the NPT that allows the P5 to ignore their obligation to disarm, and to decide how NNWS can be punished for ignoring their obligations. In light of this, can the NPT be sustained as the heart of the international non-proliferation regime? Can it be amended to hold the P5 more responsible for disarmament? Can equitability be found in a system that allows certain states to have nuclear weapons, but forbids others to have them? Does referring non-compliant states to the UN Security Council ultimately prevent or encourage these states to continue developing nuclear weapons

Delegates are asked to discuss the current state of NPT enforcement, and how it reflects the international climate from which it emerged (1960’s/70’s). Additionally, delegates are asked to consider whether the current non-proliferation regime can be sustained by the NPT as it stands now, or if measures must be taken to improve equitability, and the equal treatment of all three of its pillars.

The strength of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has often been said to be rooted in its near universal acceptance worldwide. However, its greatest weakness can also be said to be in the few exceptions. Most notably, Israel, Pakistan and India, all of whom possess nuclear weapons, stand as challenges both to the treaty and the nuclear non-proliferation regime as a whole. Furthermore, nuclear collaboration between these states and NPT parties (such as those proposed between China and Pakistan, and the US and India) stand to further compromise the authority of the treaty. It has also been said that the refusal of the P5 to condemn Israel’s nuclear program, while placing ever increasing sanction on Iran for its believed nuclear weapons program, accents the inherent inequality that arises from non-universality. If you are a decision maker seeking universality in the non-proliferation regime, how would you convince these non-NPT parties to join the regime? Can they be accepted as NPT recognized nuclear weapons states? Do they need to be parties to the NPT to be considered part of the non-proliferation regime? Can any or all of them be convinced to join as non-nuclear weapons states under the current norms of the NPT? Is there a third category under the NPT that these states might eventually belong to?

Delegates are asked to discuss the effect of non-universality on the effectiveness of the NPT, and the strength of the non-proliferation regime at large. Consider specific instances of double standards, such as in South Asia and the Middle East. Additionally, delegates are asked to consider possible mode of including non-NPT states more actively in the non-proliferation regime.

Nuclear Black Market Committee

There is one incident detected per year, on average, of stolen radiological material from inside the former Soviet Union. In addition, there have been cases of disgruntled workers inside the American nuclear establishment who have also tried to use their access to sell nuclear materials on the black market. In addition to the incidents recognized by the IAEA, there are also those that are still classified and additional undetected incidents. Compounding the threat from existing nuclear power plants, we are now in an age that many are calling the Nuclear Renaissance, with tens of countries exploring the idea of nuclear power. The recent turmoil in Arab countries has highlighted the risks posed by nuclear energy in politically unstable countries. If material cannot even be completely tracked in developed countries, what is the likelihood of theft if nuclear programs take root in developing countries? The physical nature of these materials makes theft easy and tracking very difficult. While there is no one solution for all countries, delegates are asked to consider how to strengthen the security regime around nuclear materials in countries that currently have nuclear programs and those that are looking to acquire them. What sort of metrics should be used to prevent theft? Would an international fuel bank aid efforts to track enriched materials? What are the best practices from the United States’ experience inside the former Soviet Union and how can they be applied to countries who desire a nuclear power program?

Delegates are asked to create an international safeguard standards and a security regime for nuclear research and energy reactors

In 2004 it was revealed that Abdul Qadeer Khan had been selling his nuclear wares outside of the existing nonproliferation regime. Using contacts forged from his work at Urenco, Khan used a network of suppliers in the US, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland to supply Pakistan with nuclear equipment. He would later sell technology to Iran, Libya, and North Korea. Khan would often exchange his wares for North Korean missile technology. Khan Research Laboratory went to far as to produce a brochure for interested countries. This gross skirting of the nonproliferation regime shows how the existing system is no longer adequate for controlling new nuclear trade. North Korean engineers have been sighted living in Iran, ostensibly to help the country build medium- and long-range missiles. But the growing suspicion is that the relationship has now expanded beyond missiles, and that the two nations are warily dealing in the nuclear arena as well. There is what Ashton Carter, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics, calls ''substantial technical cooperation among all members of the brotherhood of rogues.'' How can the lessons of the AQ Khan network be applied to prevent existing and future black markets? Is it possible to create an international intelligence agency, or at least an organization where members of various national intelligence agencies can share information and work together on this mutual threat? Can the NPT and Nuclear Suppliers Group be adapted to better control the actual acquisition of weapons-usable material? What changes need to be made to export controls?

Delegates are asked to create international guidelines to contend with the black market, keeping in mind that parts of it may be state supported. What sort of punishment is appropriate for black market operators, how can states be induced to comply with the new standards, and what body will hold this authority?

The nuclear black market can be divided among between the supply side, demand side, and intermediaries. Most nuclear smuggling has been caught when the material was still with the supply side. This can mean anything from nuclear plant workers to the AQ Khan network. Intermediaries are often organized crime groups who also deal in drugs and weapons. Their smuggling expertise lends them an advantage in transporting the material. The demand side includes terrorists, separatist movements, and potentially other states. It is known that some of the leading scientists in Pakistan’s nuclear program met with al Qaeda representatives and Chechen rebels have also tried to acquire nuclear materials. In what ways do these various steps in the black market need to be combated to hinder and eliminate the black market? How can border security be strengthened? How can corruption be reduced among border agents along known nuclear smuggling routes such as Central Asia and Eastern Europe? Are sting operations helpful? Or do they merely increase the perceived demand and increase the level of smuggling?

Delegates are asked to enhance border security measures and export controls, as well as think of related anticorruption measures.

Nuclear material is difficult to track by nature. Nuclear power plants and enrichment facilities expect small margins of uncertainties in their operations, which can hide the effect of a thief. Uranium and plutonium are easy to hide, coming in various concealable forms like powders, washer sized disks, and pellets. The collapse of the Soviet Union was the worst case scenario for the security of thousands of tons of HEU and weapons grade plutonium. The Cooperative Threat Reduction was a response to this risk and was an outstanding success. It dismantled thousands of warheads, hundreds of missiles, and tens of nuclear submarines in the former Soviet Union. Yet there are still insecure sites with hundreds of pounds of weapons grade material all across the world. There are no binding global nuclear security standards, and some sites are so appalling that dead rats are floating in the fuel pools. How can standards be developed for handling and dismantling nuclear materials and then be adopted by tens of countries? How can industry leaders from all countries gather to share best practices? In the long term, is the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty the only way to prevent further proliferation of nuclear materials? What conditions need to exist in order for countries to agree to the FMCT?

Delegates are asked to consider the possibility of a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty and decide whether the current nonproliferation regime is the best one for the current century. ]

Economic Impact Committee

Because a nuclear terrorist attack has thankfully never occurred, all analysis of the economic impact of such an even is theoretical. We can turn to analyses of the effects of other types of terrorist attacks, and hypothesize from there. Depending on the location of any potential attack, the economic impact can range from the destruction of the local economy, to worldwide financial institutions. Psychology will very likely play a role. Infrastructure used to facilitate economic activity, such as transportation centers may be destroyed. The world’s food security and the relating economic institutions will be impacted. What would the direct economic implications be of a potential attack? How might those effects rippled to reach your nation?

Delegates are asked to assess the damage that may be done to the global economy on local, national, and international levels and to consider what safeguards need to be put in place in advance of any such attack.

In crisis management, world leaders must act fast in order to prevent the damage from getting worse than it has to be. Based on your impact assessments, what actions would need to be taken immediately after a potential attack to salvage the economy? Whose responsibility would each action be? What could your nation contribute to these efforts? What would your interests be, and who might be your allies in achieving them? To what extent would a coordinated global approach be needed, and to what extent must nations act independently?

Delegates are asked to examine the actions necessary to respond effectively to the economic impacts of the attack.

Resilience is the ability of an institution to withstand disruption and continue to function. For example, a resilient economy will have a diverse set of income sources, so that if one has a bad year, the others can still support the population. A diverse government has the support of its people, and a set of procedures for all conceivable eventualities, including the loss of its leaders. Having assessed and responded to the potential impact of an attack, what gaps exist in the world’s economies that might allow them to be hurt by the attack? How can these gaps be repaired in preparation for future attacks?

Delegates are asked to assess the resilience of the world’s economies and make recommendations to fix them.

Food security is an ever-present issue in a world with a rapidly growing population and a rapidly shrinking supply of arable land, clean water, and willing farmers. A nuclear attack would most likely pose huge new food security issues. The location of the attack would dictate the exact effects, but they may include: radiation poisoning of farmland, destruction of food processing or transportation infrastructure, and/or an increased need for food aid to the affected nation. On an economic level, the agriculture industry is an important component of many nations’ GDPs. Additionally, the amount of food a nation must import and can output would very likely be affected.

Delegates are asked to plan for the future of global agriculture and food security in the event of a nuclear attack.

Global Disarmament Committee

One of the main pushes for global nuclear disarmament in the international community is through the Fissile Material Cutoff (FMCT) Treaty. The FMCT seeks to prohibit further production of fissile materials for nuclear weapons and other explosive devices. The intention of the FMCT is to gradually age out nuclear weapons technology and in doing so actualize the goal of Article VI of the Non-Proliferation treaty where nuclear weapons states (NWS) seek in good faith to disarm their nuclear arsenals. One of the issues in the FMCT is the difference in opinion as to what actually constitute fissile material. On March 3rd, 2011, US Ambassador Laura Kennedy issued a statement to the Conference on Disarmament calling into question the definition of ‘fissile material’ and how the conference can come to define it and ‘production’ in a way that will prevent countries from finding loopholes and opportunities to circumvent the FMCT. Although there is a definition of fissile material provided by the IAEA, some have argued that the IAEA definitions and categories represents only a good starting point and that some amendments need to take neptunium and americium into account. What definitions exist for ‘fissile material’ and what comprises a weak definition? Why would different countries espouse different definitions and how definition allows the trade-off where the definition is rather strict but not so strict as to get limited signatories?

Delegates are asked to propose an encompassing definition of fissile material for the FMCT that will not only maximize its effectiveness but chances of being ratified internationally.

Currently, states with nuclear arsenals like the United States have a policy calculated ambiguity as to whether or not they will respond to a nuclear, chemical or biological weapons attack with nuclear weapons attack. This policy undercuts commitments of states in the 1995 NPT extension conference to not use or threaten non-nuclear weapon states that are members of the NPT. Does the policy of calculated ambiguity reinforce the concept of nuclear weapons utility in the arsenals of NWS? Because nuclear weapons are being considered useful for the concept of calculated ambiguity, does this give non-nuclear states extra incentive to copy the models set by NWS? For countries where central government has limited control over different regions, should a non-state actor use chemical or biological weapons, will the central government be held accountable? Does calculated ambiguity help or harm disarmament?

Delegates are asked to debate the concept of calculated ambiguity in terms of its effects on global disarmament and whether there should be an international structure in place to limit this policy for NWS.

To what degree does nuclear weapons disarmament need to address proliferation of nuclear energy? Most of the nations that have acquired nuclear weapons technology have done so under the guise of nuclear energy programs. The International Atomic Energy Agency attempts to monitor the dual use technologies (technology that can be diverted between nuclear energy and nuclear weapon programs) in countries that are signatories of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Should the international community tolerate the ownership of dual use technology in a post- NYC bomb world? Will disarmament require there to be an end to the promotion of nuclear energy technology? The NPT stipulates that its member countries are entitled to nuclear energy technology as well as the assertion that nuclear weapons capable member states must make efforts in good faith to dismantle their nuclear weapons. How can the latter requirement be enforced?

Delegates are asked to assess the utility of nuclear energy programs and whether the benefits of nuclear energy overcome the costs of potential nuclear weapons. They are asked to consider whether disarmament is possible in an international system that encourages nuclear energy.

The United States maintains a nuclear weapons umbrella for its allies in East Asia such as South Korea and Japan. In return for protection underneath the United State’s nuclear umbrella, these states do not maintain nuclear weapons capabilities. To what degree is the maintenance of a nuclear umbrella counter-productive to global nuclear weapons disarmament? Although the maintenance of the nuclear umbrella has restricted program in South Korea and Japan, does the United States’ reiteration of their right to nuclear weapons allow other states to make similar claims? Should the international community encourage the break up of the nuclear umbrella in order to encourage disarmament? What role can the international community have in ending the nuclear umbrella while ensuring the safety of countries with existential threats due to other state’s nuclear programs such as the DPRK? How can the international community address Israel’s presumed nuclear program? Is this required for global disarmament?

Delegates are asked to consider what the effects of nuclear umbrellas are on disarmament. They should assess whether disarmament goals of having less states with nuclear weapons is redeemable when nuclear umbrellas make sure that the NWS will not give up their capabilities.

Contending with Failed States Committee

Many experts have wrestled with the implications of a failure of a NWS. For example, Pakistan and North Korea are often cited as being on the brink of failure. Both states suffer from weak economies and face humanitarian crises that their leaders have been either unable or unwilling to rectify. The North Korean leadership is due to change soon, Kim Jong Il’s resignation is expected in 2010 and his son Kim Jong-un, the heir apparent, will most likely transition to power. However, this transition may not go smoothly, and it is unclear exactly how a change in leadership will effect North Korea. The way that political changes in North Korea effect its relations with the U.S. and other global powers is as of yet unclear.

The delegates are asked to determine the best mechanism for promoting the safety of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

In Pakistan, religious extremism has had steadily increasing influence in recent years. Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer and Christian Minority Minister Shahbaz Bhatti, both defendors of religious tolerance in Pakistan, were murdered in the early months of 2011. Crowds of joyous Pakistanis have received their killers as martyrs. Among those who comprise this rising tide of religious extremism in Pakistan are many who aim to topple the Pakistani government. If religious extremists were to topple the Pakistani government, Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal could easily fall into the hands of religious fundamentalist terrorist groups. Though the government and military of Pakistan are aware of this threat, little has been done to fight the growing religious fundamentalism in Pakistan, yet promoting the stability of the current Pakistani government is generally seen as the lesser of two evils by the international community. U.S. and Pakistani intelligence collaboration has been key to preventing threats to Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal in recent years. However, Pakistan’s detention of CIA agent Raymond Davis after his killing of two Pakistanis in January 2011 has dealt a grave blow to relations between the intelligence establishments in the U.S. and Pakistan. Experts are doubtful that relations between the U.S. and Pakistan will recover quickly from this incident, which is so far unresolved. What is the international community’s role in promoting stability in Pakistan? Will another government be willing and capable of working with Pakistan’s ISI to promote intelligence operations? How can more be done to foster cooperation between the international community and the Pakistani government and military in reversing the rising tide of Islamic fundamentalism? In addition to this, Pakistan’s nuclear weapons are often cited as being loosely controlled by the Pakistani military, and subject to theft by would-be terrorists.

The delegates are asked to determine how the international community can work with Pakistan to ensure the safety of its nuclear arsenal. In the case of a state collapse, who will assume responsibility for the safety of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons? In the case of Pakistani state failure, which powers would be willing and capable of restoring order? How would this effect regional dynamics?

The collapse of a weapons state is not the only threat. Many potentially unstable states that operate nuclear power plants have significant amounts of nuclear material, some of which is sufficiently enriched for use in nuclear bombs. The regions of Eastern Europe and the Middle East have proven volatile in recent years, and many states in these regions rely on nuclear power. Consider what the consequences could have been if Libya had significant amounts of nuclear material during the turmoil that has transpired there in recent weeks. Consider the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, a country dependent on nuclear energy, and what the consequences could be if a state in a similar situation faced collapse. In the event of state collapse in a country with sensitive nuclear weapons materials and technologies, how will the international community work to ensure the security of these technologies and materials?

The delegates are asked to determine what steps need to be put in place to ensure, globally, that fissile materials are always safeguarded.